December 12, 2025

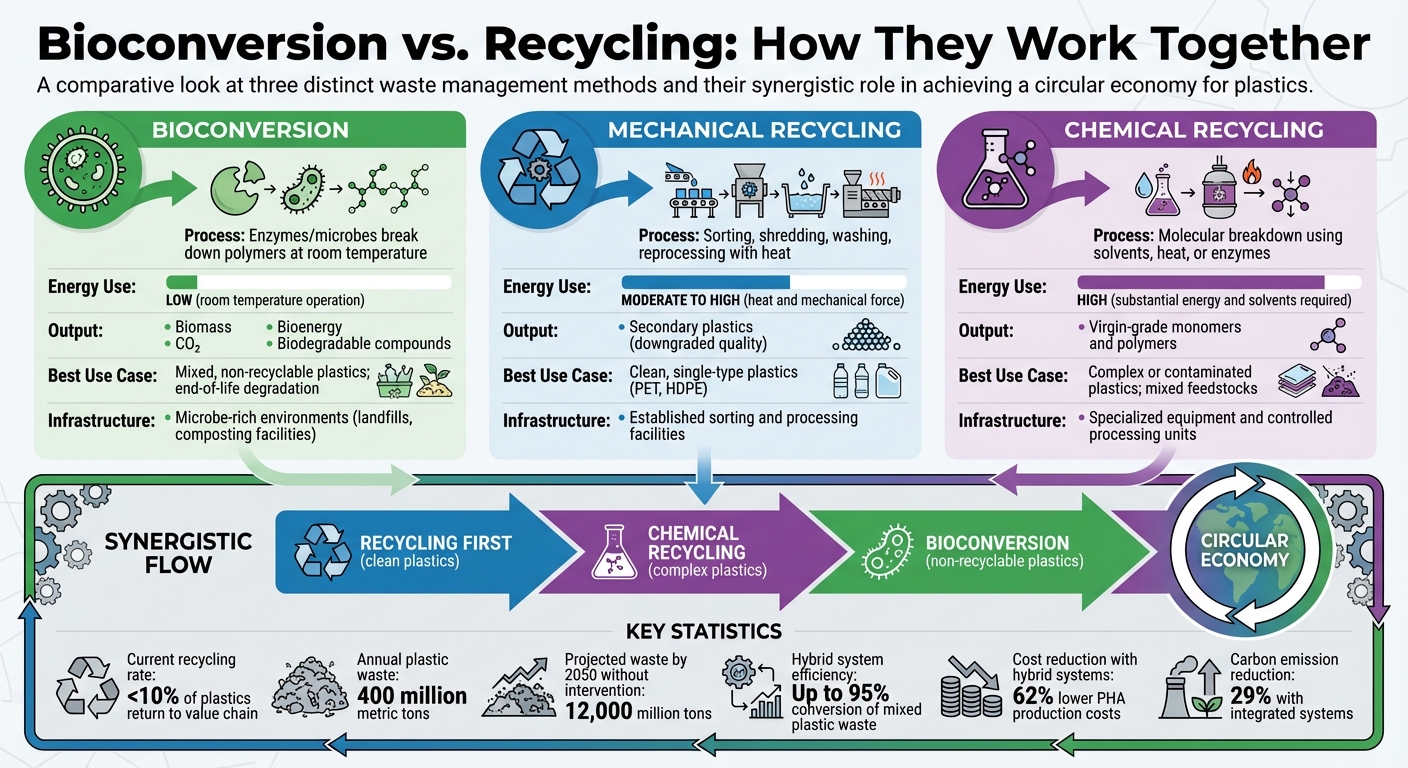

Plastic waste is a growing issue, and no single solution can address it all. Recycling and bioconversion are two distinct yet complementary methods that, when combined, can close the loop on plastic waste.

Both approaches have unique strengths and limitations. Recycling is ideal for clean, single-type plastics, while bioconversion excels with complex or non-recyclable materials. By integrating these systems, we can create plastics with multiple end-of-life pathways, ensuring they are reused, recycled, or broken down efficiently.

Quick Comparison:

| Factor | Bioconversion | Mechanical Recycling | Chemical Recycling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process | Enzymes/microbes break down polymers | Sorting, shredding, reprocessing | Breaks plastics into monomers |

| Energy Use | Low (room temperature) | Moderate to high | High |

| Output | Biomass, CO₂, bioenergy | Secondary plastics | Virgin-grade materials |

| Best Use Case | Mixed, non-recyclable plastics | Clean, single-type plastics | Complex or contaminated plastics |

Bioconversion vs Recycling Methods: Process, Energy Use, and Applications Comparison

Bioconversion relies on enzymes from microbes to break down polymer chains into smaller, simpler molecules. In environments rich in microbes - like landfills or soil - bacteria, fungi, and algae attach themselves to the surface of plastics and release enzymes that start breaking the polymers apart. Through a process called hydrolysis, these complex polymers are gradually reduced to basic components like water, carbon dioxide (CO₂), and biomass. This step-by-step breakdown creates the perfect conditions for biodegradable additives to speed up the degradation process.

Traditional petroleum-based plastics are incredibly durable because their molecular structures resist microbial enzymes. Biodegradable plastic additives solve this issue by kickstarting the hydrolysis process, making it easier for microbes to digest the material. For instance, BioFuture Additives' solutions are added during the manufacturing phase without disrupting production or weakening the plastic. Once these treated plastics end up in microbe-heavy environments, the additives help convert them into non-toxic biomass.

Bioconversion isn't just a technical process - it has meaningful environmental benefits. By breaking plastics down into their basic elements, it reintegrates them into the carbon cycle, aligning with efforts to create a more sustainable future.

Mechanical recycling involves taking plastic waste and turning it into secondary raw materials without altering its chemical structure. This process includes sorting, shredding, washing, drying, and reprocessing the plastics while keeping their polymer chains intact.

The downside? Each recycling cycle weakens the plastic. Heat and mechanical stress break down the polymer chains, causing oxidation and reducing the material's quality. This degradation often leads to downcycling - where a plastic water bottle, for instance, ends up as a park bench rather than being turned into another bottle. Contamination also poses a big hurdle. Sorting errors can introduce food residue, labels, or mixed plastics, making it harder to produce usable recycled materials.

Unlike mechanical recycling, chemical recycling breaks plastics down to their molecular components. By using solvents, high heat, enzymes, or even sound waves, these methods transform plastics into monomers, polymers, or hydrocarbon products that can be reprocessed into virgin-grade materials. Techniques like pyrolysis and depolymerization essentially reverse the plastic production process, creating high-quality materials rather than downgraded ones.

But this method comes with its own set of challenges. Chemical recycling requires substantial energy, large amounts of solvents, and expensive equipment. While it can handle mixed or contaminated plastics that mechanical recycling can't, the infrastructure to support it is limited and costly. These factors make chemical recycling less accessible on a large scale, despite its potential to complement other recycling methods and contribute to a more sustainable system.

In the U.S., recycling infrastructure falls short of its potential. A large portion of plastic waste ends up in landfills instead of being recycled. The plastics that do go through the system are mostly PET (like water bottles) and HDPE (like milk jugs), as these are the easiest and cheapest to process. Other types of plastic face significant obstacles, including limited sorting technology, contamination, and insufficient processing capacity. This creates a system that effectively handles only a small fraction of plastic waste, leaving the majority of materials produced and discarded every day outside its reach.

Bioconversion and recycling tackle plastic waste in distinct ways, each contributing to a more sustainable approach to managing materials. Bioconversion relies on biological agents, such as enzymes or microorganisms, to break down plastics into biodegradable compounds, bioenergy, or other usable byproducts. This method supports eco-friendly disposal for plastics that might not fit traditional recycling systems. Recycling, on the other hand, focuses on reclaiming plastics through mechanical or chemical processes that allow the materials to be reused in manufacturing new products.

One key difference lies in energy use. Bioconversion processes often work at room temperature, which results in very low energy consumption. In contrast, recycling methods - whether mechanical or chemical - typically require significant energy due to the need for heat, mechanical force, or specialized solvents. While recycling excels at keeping materials in circulation, bioconversion provides a solution for plastics that are not recyclable through standard methods. The table below highlights the main distinctions between these approaches.

| Factor | Bioconversion | Mechanical Recycling | Chemical Recycling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process | Enzymatic or microbial breakdown at room temperature | Sorting, shredding, washing, and reprocessing with heat | Molecular breakdown using solvents, heat, or enzymes |

| Energy Requirements | Extremely low (room temperature operation) | Moderate to high (involves heat and mechanical force) | High (requires substantial energy and solvents) |

| Material Output | Biodegradable compounds, bioenergy, bioproducts | Secondary plastics | Monomers or polymers suitable for new production |

| Infrastructure Needs | Environments that support microbial activity (e.g., landfills, composting facilities) | Established sorting and processing facilities | Specialized equipment and controlled processing units |

| Best Applications | End-of-life degradation and plastics unsuitable for conventional recycling | Clean, single-type plastics (e.g., PET, HDPE) | Mixed plastics or feedstocks that are challenging to sort |

These differences make it clear that combining both methods can improve how we manage plastic waste. Together, bioconversion and recycling create multiple options for handling plastics at the end of their life.

Despite their benefits, some misunderstandings surround bioconversion and recycling. For instance, bioconversion isn’t a replacement for recycling - it complements it. This method is particularly useful for plastics that cannot be processed through traditional recycling. Even plastics with biodegradable additives can enter recycling systems, with bioconversion stepping in only when recycling is less effective.

The term "bioplastic" often adds to the confusion. Many assume that all bio-based plastics are automatically more sustainable than those made from fossil fuels. However, this isn’t always the case. The full environmental impact, including the production and disposal stages, must be considered to evaluate sustainability.

Another common misconception is that waste has no economic value, leading to its disposal rather than its transformation into something useful. Both bioconversion and recycling challenge this outdated idea by turning waste into valuable outputs - whether it’s recycled materials, bioenergy, or biodegradable compounds. The goal isn’t to pick one method over the other but to identify the best solution for different types of plastic waste.

Designing plastics with multiple end-of-life options - such as reuse, mechanical or chemical recycling, and bioconversion (like composting or anaerobic digestion) - is key to achieving circularity. These designs must align with U.S. waste management systems to ensure their effectiveness.

To reach net-negative emissions for plastics by 2050, an integrated approach is essential. This includes combining bio-based plastics, renewable energy, and advanced recycling methods. Plastics enhanced with biodegradable additives offer flexibility: they can enter recycling systems when possible or be broken down through bioconversion in environments where traditional recycling is impractical, such as landfills or oceans. This multi-pathway approach lays the groundwork for hybrid systems that aim to recover as many resources as possible.

Hybrid systems take a flexible approach to managing plastic waste. They prioritize mechanical or chemical recycling for clean, recoverable materials. When plastics are too contaminated, degraded, or unsuitable for conventional recycling, bioconversion provides a valuable alternative.

These systems are particularly efficient: integrated chemical-biological processes can convert up to 95% of mixed plastic waste into monomers. This approach reduces PHA production costs by 62% and cuts carbon emissions by 29%. Hybrid systems can handle diverse plastic types - such as PET, PLA, HDPE, and polystyrene - without the need for expensive sorting steps. By eliminating intermediate separation processes, these methods lower complexity and costs while maintaining environmental benefits. Additives that enhance compatibility with both recycling and bioconversion further improve the efficiency of these systems.

BioFuture Additives play a crucial role in making plastics fully recyclable while also offering a bioconversion option for materials that escape collection systems or reach the end of their lifecycle. These biodegradable additives are designed to work seamlessly with current recycling processes, ensuring consistent results across both recycling and bioconversion pathways. Their effectiveness has been demonstrated in production lines worldwide, including in North America, Europe, Latin America, and Asia.

This technology supports traditional recycling efforts while providing a backup option for unrecovered waste. By enabling dual functionality, BioFuture Additives help companies achieve Scope 3 emissions targets and circularity goals without requiring changes to existing manufacturing processes. The result is a system where plastics have multiple viable end-of-life options, ensuring maximum resource efficiency no matter where the material ends up.

Bioconversion and recycling are two powerful tools working together to support a circular economy for plastics. Recycling - whether mechanical or chemical - keeps plastics in use by either converting them into secondary raw materials or breaking them down into monomers for new products. On the other hand, bioconversion uses biological processes, where microorganisms transform polymers into monomers or other useful products like PHAs, which can then be used to create new plastics.

Currently, less than 10% of plastics make their way back into the value chain, while an enormous 400 million metric tons of plastic waste are produced every year. Neither recycling nor bioconversion alone can tackle this challenge. Recycling is effective for clean plastics, while bioconversion excels at managing complex waste. Combining these approaches is critical - especially when projections suggest that, without intervention, 12,000 million tons of plastic waste could end up in landfills or the environment by 2050.

The bioplastics market is expanding at twice the pace of fossil-based plastics, indicating a growing shift toward regenerative solutions. As Emmanuel Ladent, CEO of CARBIOS, aptly put it:

"Plastic circularity's future will be biological. It will drastically cut our reliance on fossil fuels".

Additionally, thoughtful product design is essential. Materials must be compatible with multiple recovery pathways from the beginning. By combining recycling and bioconversion, we can create more end-of-life options, reinforcing the circular lifecycle that’s crucial for sustainability. These strategies point toward actionable solutions for businesses and industries.

Take these insights and put them into action. Start by designing products with multiple end-of-life pathways in mind. This means optimizing material composition and structure to ensure compatibility with both recycling and bioconversion processes. Tools like BioFuture Additives simplify this process, allowing plastics to perform well in both systems without requiring changes to existing manufacturing setups.

Consider investing in technologies that integrate both recycling and bioconversion methods. By doing so, you’ll improve waste recovery and support a circular economy. With plastic waste and regulatory pressures increasing, businesses that adopt integrated waste management strategies will be better positioned to meet sustainability targets and satisfy consumer expectations.

Bioconversion and recycling join forces to address plastic waste while advancing a circular economy. Bioconversion relies on natural processes, such as enzymatic or microbial breakdown, to convert non-recyclable plastics into biodegradable materials or useful byproducts. Recycling, in contrast, focuses on reprocessing plastics into new materials while retaining their quality and functionality.

When combined, these approaches help cut down on landfill waste, conserve resources, and lessen environmental harm. By pairing bioconversion for plastics that are tough to recycle with advanced recycling methods, we can adopt a more sustainable way to manage the lifespan of plastics.

Recycling plastics, whether through mechanical or chemical methods, comes with its fair share of challenges.

Mechanical recycling often runs into issues with contamination. When plastics are mixed or dirty, the quality of the recycled material can drop significantly. On top of that, each recycling cycle tends to weaken the material, eventually making it less functional and harder to reuse effectively.

On the other hand, chemical recycling has its own set of obstacles. While it can break plastics down into their original components, the process demands a lot of energy and can be expensive. Plus, it may release greenhouse gases and generate hazardous byproducts, adding both environmental and financial complications. Scaling up these technologies to handle global plastic waste remains a daunting task, making it tough to achieve a truly circular system for plastics.

Creating plastics with various end-of-life possibilities is key to cutting down waste and lessening the strain on our planet. By enabling materials to follow different disposal routes - like recycling, bioconversion, or biodegradation - we can reclaim valuable resources while keeping plastics out of landfills and away from natural habitats.

This strategy aligns with the idea of a circular economy, where materials are reused or repurposed to extend their usefulness and preserve natural resources. By designing plastics that can fit into multiple disposal systems, we not only make waste management more versatile but also prepare for the changing demands of sustainability.